About ALPS

|

ALPS is the Alpine Lakes Protection Society. The name is not because we are specifically about protecting lakes (although we do that too,) but from the "Alpine Lakes" region of the central Cascades east of Seattle. The Alpine Lakes region is generally considered to be that part of the Cascades between, and including, the Highway 2 (Stevens Pass) corridor and the Interstate 90 (Snoqualmie Pass) corridor, as well as lands extending for some ways north and south of these.

ALPS takes an interest in just about everything that goes on in these parts of the Cascades. In the early years, from 1968, ALPS led the successful campaign to designate the Alpine Lakes Wilderness, now comprising almost 400,000 acres. In more recent years, the ALPS areas of concern have broadened considerably. It might be more appropriate to say that ALPS now works to protect conservationist values across the entire central Cascades. The designation of the Alpine Lakes Wilderness in 1976 was a great victory, but it can also be looked upon as a first step. Since then, ALPS has played a major role in every conservation issue affecting the central Cascades. We have played a big part in stopping the liquidation of forests on public lands, especially the Mt. Baker Snoqualmie National Forest on the west side and the Okanogan-Wenatchee National Forest on the east side. ALPS has also been very involved in consolidating the once fragmented land ownership patterns in the Cascades. We have worked to locate, plan and develop new trail opportunities. We are working to add new lands to the Alpine Lakes Wilderness, and have worked extensively with the Washington Department of Natural Resources (DNR) to protect and develop recreational opportunities on state lands. ALPS will continue to be involved in everything to do with conservation in the central Cascades, development of sustainable recreation opportunities there, and much more. We invite your help. Please contact alpinelakes.info@gmail.com. |

History of Alpine Lakes

|

Engineers planned highways to slice through the de facto wilderness near Lake Dorothy and over Van Epps Pass. The Alpine Lakes was in danger of being chopped, roaded, and logged to death.

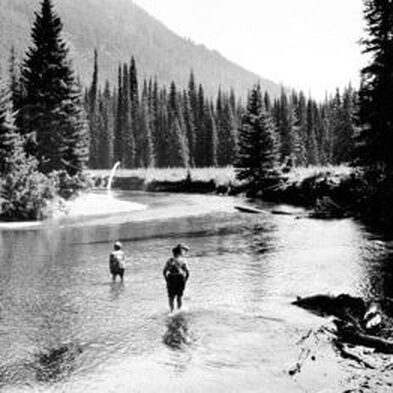

The need for specific defenders became obvious. A small group of conservationists in the Seattle area began to meet and talk about it. They learned of a similar group in Ellensburg. On a rainy October Sunday in 1968 the two groups met, took a soggy hike together, held a meeting at Salmon La Sac along the Cle Elum River, and formed Alpine Lakes Protection Society, or as everyone still calls it, "ALPS".

The need for specific defenders became obvious. A small group of conservationists in the Seattle area began to meet and talk about it. They learned of a similar group in Ellensburg. On a rainy October Sunday in 1968 the two groups met, took a soggy hike together, held a meeting at Salmon La Sac along the Cle Elum River, and formed Alpine Lakes Protection Society, or as everyone still calls it, "ALPS".

|

Created as a non-profit corporation under Washington law, ALPS started with chapters in Seattle and Ellensburg. New members soon added chapters in Wenatchee and the Seattle suburbs east of Lake Washington. Many of the officers of ALPS, called "trustees", were new as conservation activists. They brought enthusiasm, but needed long hours of discussion to resolve what ALPS should try to do. The more they learned about the Alpine Lakes area, they more they realized how complex the task would be.

|

Out of this process eventually came a plan. First, the trustees agreed that the political boundaries that split the area into separate national forests and counties confounded the need for unified, coherent management. Second, they agreed that the area's roadless core needed formal protection as a Wilderness area, designated by Congress under the Wilderness Act. The third big point was the most controversial.

The ALPS trustees decided that the intermingled public and private lands around the wilderness core needed protection too, and the best way to ensure it was to ask Congress to create an Alpine Lakes National Recreation Area.

For six tumultuous years ALPS led an intense congressional campaign, aided by environmental and non-environmental allies, to reach that goal. ALPS members testified, wrote letters, and lobbied. The final result was the Alpine Lakes Area Management Act of 1976, now codified in notes following 16 U.S. Code § 1132. That federal law met two of the three goals ALPS had sought. It called for unified management, and it created a 393,000 acre Alpine Lakes Wilderness. It also included some innovative approaches for acquiring private lands within that Wilderness. But instead of a national recreation area, Congress created a "management unit" around the Wilderness, a compromise that fell short of what ALPS thought the area needed.

The ALPS trustees decided that the intermingled public and private lands around the wilderness core needed protection too, and the best way to ensure it was to ask Congress to create an Alpine Lakes National Recreation Area.

For six tumultuous years ALPS led an intense congressional campaign, aided by environmental and non-environmental allies, to reach that goal. ALPS members testified, wrote letters, and lobbied. The final result was the Alpine Lakes Area Management Act of 1976, now codified in notes following 16 U.S. Code § 1132. That federal law met two of the three goals ALPS had sought. It called for unified management, and it created a 393,000 acre Alpine Lakes Wilderness. It also included some innovative approaches for acquiring private lands within that Wilderness. But instead of a national recreation area, Congress created a "management unit" around the Wilderness, a compromise that fell short of what ALPS thought the area needed.

|

Still, many people felt ALPS had accomplished its goal. Some even suggested, with nothing more to do, it could disband. But the trustees, battle-hardened from their congressional campaign, knew differently. Given the area's scenic and recreation attractions, proximity to so many people, and array of competing interests, they knew the Alpine Lakes area still needed a specific defender. And without a national recreation area to provide overall guidance, they knew resource conflicts, like mushrooms after rain, would keep cropping up. Moreover, the checkerboard land ownership pattern, created by the railroad land grant of the late 1800s, still plagued the area. A century later, those alternating sections of private land, now in the hands of big timber companies, complicated wildlife, recreation, and watershed protection, and reduced management options to their lowest common denominator. Thus ALPS decided to stay in business. It adapted to a new, less glamorous, but equally important role. Its first big post-legislative effort was to monitor and comment on the area's first overall management plan, adopted in 1981.

|

Efforts then turned to correcting the checkerboard ownership pattern. ALPS started to lobby Congress for funds to buy private lands. It worked with the Forest Service and private owners to facilitate land exchanges. Its first major success was with an exchange and purchase package that removed Longview Fibre Timber Co. Since then, ALPS efforts have focused on land ownership in the Cle Elum area, where ALPS and its allies convinced Congress to fund a major purchase of sections that has made possible the consideration of certain additions to the Wilderness. On other fronts, ALPS tracked land use proposals and resisted those that seemed unwise. Where necessary, it resorted to appeals and courts. ALPS lost some of these brushfires and won others. Its list of victories would be long. Some are permanent -- disputed lands have been acquired, proposals have been modified to meet objections -- others are temporary and could flare up again. Throughout this process, ALPS gained the respect of the Forest Service and large landowners. It has a tradition of studying and taking positions only after they are researched and thought out. It avoids knee-jerk reactions. ALPS has focused exclusively on the Alpine Lakes, which gives it in-depth knowledge few others can match. Forest Service managers may come and go, but the trustees and members of ALPS have accumulated decades of on-the- ground intelligence.

Challenges still abound. The Alpine Lakes is now part of a grizzly bear recovery area, typifying a new focus on wildlife issues. The Bush Administration is trying to reverse key forest management policies. Logging, roads, and mining loom as bigger issues in the future. And people pressures keep mounting, highlighted by a new resort along the southern edge of the Alpine Lakes between Cle Elum and Roslyn. The challenges have changed, but the need for an Alpine Lakes Protection Society remains as critical today as it was back in the 1960s.

Challenges still abound. The Alpine Lakes is now part of a grizzly bear recovery area, typifying a new focus on wildlife issues. The Bush Administration is trying to reverse key forest management policies. Logging, roads, and mining loom as bigger issues in the future. And people pressures keep mounting, highlighted by a new resort along the southern edge of the Alpine Lakes between Cle Elum and Roslyn. The challenges have changed, but the need for an Alpine Lakes Protection Society remains as critical today as it was back in the 1960s.

Trustees

|

Rick McGuire, President

Frank Swart, Treasurer Natalie Williams, Secretary Vertical Divider

|

Thom Peters

Gus Bekker Sarah Guarracino Vertical Divider

|

|